The Rev. Dr. William J. Danaher, Jr.

Transcription

Sermon

Mark 1:29-39

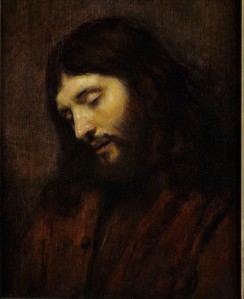

In the 1640’s and 50’s Rembrandt van Rijn, the Dutch artist, began to do something different. He and his studio began to paint these different portraits of Jesus—of his face. And where in Western art there had been the tradition of depicting Jesus as a kind of cosmic deity carved out of marble or some kind of idealized figure that was beautiful and barely touched the ground, these new faces of Jesus were taken from local Jews that lived in their neighborhoods. These were people that they saw and often looked past. And these faces of Jesus had their own kind of radiance. It was the radiance of their ethnicity, the radiance of their identity, the radiance of their humanity.

And so the paintings had this incredible power, and they were controversial. They disrupted the way in which people tended to see Jesus. Jesus was no longer understood in terms of his ecclesiastical offices of prophet, priest or king. He was rather Jesus as he appears to us in all of his vulnerability rather than his invincibility, in all of his vulnerability as a human being, truly human as he is truly divine.

These paintings have long captured my imagination. I know that the DIA in 2011 did a remarkable retrospective of them, together with a museum in Philadelphia and Washington DC; it went all over. And it was powerful. And there, the emphasis was on Jesus’ ethnicity: They took Jewish figures to depict Jesus to a Western Christian culture.

But I want to also look at two other things that are important in these paintings. The first is the interplay of light and darkness. Rembrandt and his followers used a technique called “chiaroscuro,” which is Italian for lightness and shade or brightness and shade. They depicted Jesus’ face so that he would be radiant yet surrounded by darkness.

And the second thing I want to point out in these paintings—that I think people have missed—is that there is this sense in the face of Jesus that he is going on to something deeper and more troubling. This Jesus has a past. He has an ethnicity. He has an identity. But also, you can see in these paintings the fact that he has a future. He has yet to be betrayed, to be mocked, to be crucified. He has yet to rise from the dead. The Jesus we meet in these painting proceeds by faith and not by sight. And therefore, he is like so many of us. Yet this Jesus is at the same time somehow foreshadowing on his very features that future.

These faces of Jesus are written with pain and suffering. He is a tired young man, looking out in many of them for some kind of connection or acknowledgment. I have given you one of these portraits today in your bulletin, and I invite you to pull it out and take a look at it when we talk about today’s Gospel.

This particular portrait was done in 1655, and it’s a little bit different from the others. It has Jesus with his eyes closed, and yet his face is bathed in light. He is emerging from the darkness. I’d like to think that this is something like what the apostles saw when, as we read in today’s Gospel, they went looking for Jesus in the midst of that darkness and found him in a deserted place, praying.

For us and for the way this Gospel touches us today, I want to suggest that the key pivot point in the scriptures that we need to attend to is that Jesus is there praying. And I want to suggest that we have to attend to it because it links together an otherwise confusing passage in Mark. It makes a connection that is not always clear.

In the first part of the passage, Mark talks about Jesus healing Simon Peter’s mother-in-law from a fever. And then there is a moment in which the entire town is gathered around him. And then suddenly, before anybody else knows what’s happening, the disciples are hunting for Jesus. They don’t know where he is. And Jesus tells his disciples that they have to come with him and move on to other cities in Galilee to proclaim his message: “For this is what I am here to do,” he says.

Tying together all these little scenes is light and darkness. When Jesus heals Simon Peter’s mother-in-law, we are told that it is daytime. In the evening, all the sick and the possessed come to see him. And then before dawn, while it is still very dark, Jesus goes and prays. And finally, the next day, Jesus tells his disciples that their mission is to carry them beyond.

There is, in other words, in this passage, a play of light and darkness. And that is what holds it together. And that is the message I think you and I need to take away from this Gospel today. Jesus is present in light, in all the things that are associated with light. Jesus is present in life and healing, and reconciliation and justice. And Jesus is also present in darkness, in everything that is associated with darkness, such as death, and sin, and disease and disgrace. And the fundamental point of this gospel, the power that it gives us, the Good News that it delivers is that Jesus walks with us in both light and darkness. Jesus is able to reconcile light and darkness like no one else.

So that’s why I think there’s something more going on in Rembrandt’s portrait of Christ praying here. I think that the light and the darkness together are meant to highlight a kind of peace that prevails in spite of any chaos, a kind of justice that will be vindicated no matter what happens in the meantime. You and I are invited today to walk by that light. You and I are invited to look for Christ as he waits for us, praying in the darkness, so that he might lead us to light. And that is good news.

In the Confessions, which Augustine completed in the year 400, he writes a prayer that takes up all of these themes. This is what he writes: “Hearken, O Lord, have mercy, My Lord and God. O Light of the blind, strength of the weak, who yet our light to those who see and strength to the strong. Hearken to my soul. Hear me as I cry from the depths. For unless your ears be present in our deepest places, where shall we go and we there cry. Yours is the day, yours the night. A sign from you sends minutes speeding by, spare in their fleeting course, a space for us to ponder the hidden wonders of your law. Shut it not against us as we knock.”

As we move towards Lent and Ash Wednesday and onto Good Friday and finally, to Easter Day, may you and I begin to carve out the kind of space Augustine prays for, in which we will find God as our refuge, our strength, our hope, our joy, our peace as he is in Jesus Christ. Amen.